Mable Hunter Stewart’s war effort and her fruit cake.

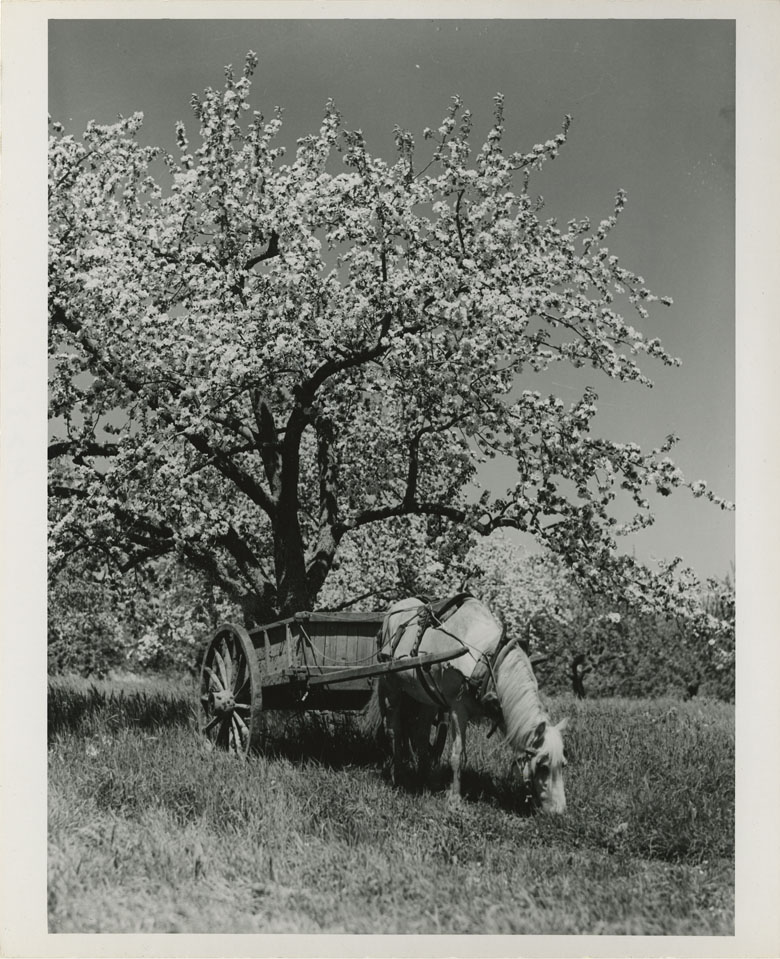

The approaching harvest, Thanksgiving and Remembrance Day draws us toward feeling gratitude for nature’s bounty, for the effort, and sacrifice of others. Fall is a sort of Gratitude season that comes scented with warm spices. This guest blog post recalls a time when cinnamon, nutmeg, and clove were more associated with molasses, candied peel, dried fruit and rum, than pumpkin.

Janet Stewart Lindstrom does not remember her Grandmother well, she was only 8 years old when Mabel died. Mabel Jewett Hunter Stewart is no mystery to Jan, her quiet goodness and steadfastness remains vivid, thanks to memories of their shared time but more directly in the quiet, steadfastness and goodness inherent in a man far more familiar, her father. Jan describes her grandmother Mabel and her father Andy as deeply proud of their Hunter Family Highland Scottish heritage as well as tried and true Royalists.

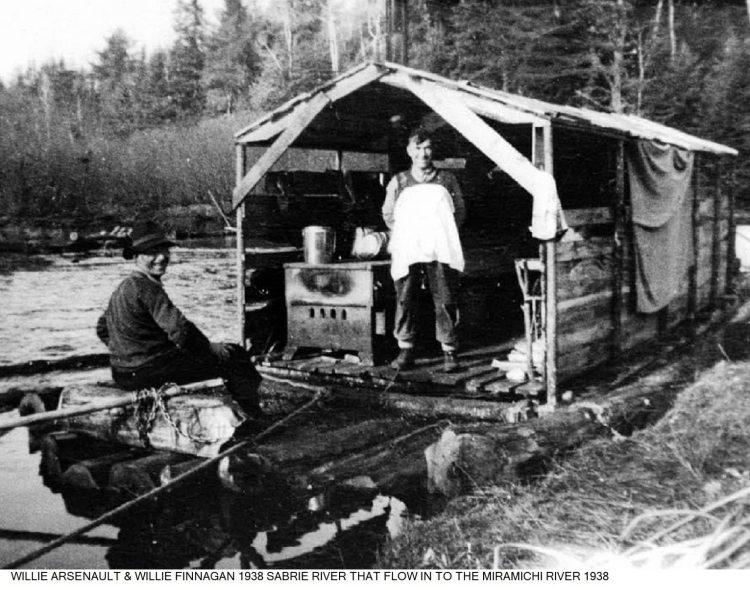

A Highlander and a Royalist? That Mabel was a Royalist is not in the least surprising, despite the complicated history between the English Crown and Highland Scots. Mabel lived thru two world wars, wars fought for King and country. Mable knew well the sacrifice families made on both sides of the Atlantic. She understood the worry, loss and grief faced by families at home and she was grateful for the young pilots and flight crews training at the nearby Moncton site of the The British Commonwealth Air Training Program (BCATP)1. Mabel knew the risk these men faced, and that there was a good chance some would die in defense of King and Country. She made her war effort a personal expression of gratitude that came flavoured with warm spices.

Jan wrote this short story about Mabel’s ‘War effort’ to share with her children and Grandchildren. I am thrilled she has agreed to share both her Grandmothers’ war effort and her recipe with My Mother’s Cookbooks.

Mabel’s War Effort…

So…you say you don’t like Fruitcake…

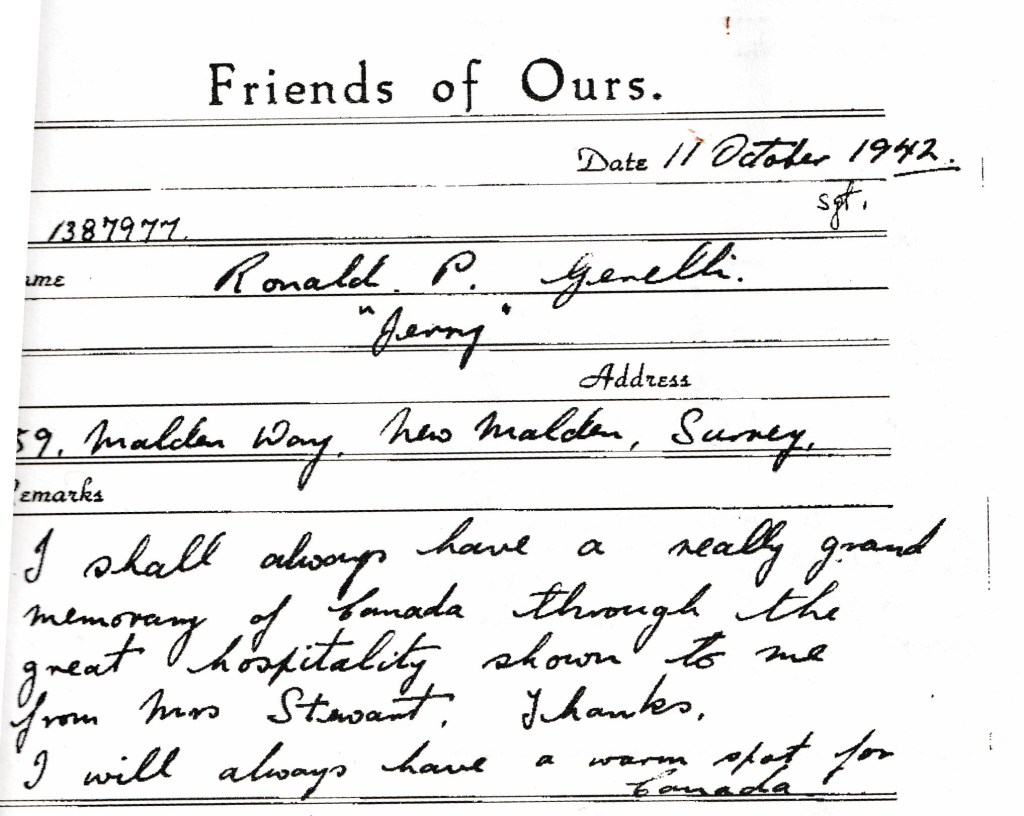

Picture this – Your Grandfather Stewart’s mother in her home in Moncton during World War II “entertaining the troops”. My Grammie at the piano playing for a sing-song, and leading good conversation, never allowing talk of religion or the war of course. This on top of serving a wonderful meal to the small groups of British airmen she hosted. My Grammie always called this her ‘war effort’. Grammie knew the young men, who were in Moncton getting their “wings” so they could return to the UK to take part in the war, would be lonesome for their families and wishing for a good family meal.

One of the highlights of the meal was the serving of a plate of her fruitcake on her prized Limoges China, just like in the photo above.

If you love a house filled with the aroma of a spicy, fruity, nut filled cake being baked or if you enjoy a quiet time with a cup of tea and a piece of cake, this cake is for you!

My love of this fruitcake is not just because it was my Grammie’s cake but because of memories of Mum and I baking it annually, in October around Thanksgiving. Why so early, if it is intended for Christmas? It gives the cake time to “ripen”, and moisten, in it’s wrapping of cheesecloth soaked in rum or brandy!

I can see the three of us, getting out the fruitcake pans and lining them with greased brown paper. The large bowl filled with the carefully measured fruit pieces coated with flour. After mixing up the cake batter in a separate bowl, the fruit was poured in, and then came my favourite part…

getting my hands right in the bowl in order to mix it all together. Messy, but fun.

Its baking for four hours filled the house with that wonderful fragrance! If we could only bottle the smell!

I wondered how long fruitcake recipes have been around? So, I checked, some historians claim fruit cakes have existed since ancient Egypt, BCE (Before the Common Era)! We are told that Roman soldiers took them into battle and that fruitcakes were taken on the Crusades in the Middle Ages.

The church had quite an influence, regularly making pronouncements the faithful were expected to honor, like in the 1400’s when they prohibited butter during Advent. The boatloads of sugar which began arriving in Europe in the 1600’s saw its use in preserving fruit including for use in cakes. In the 1800’s when the church tried to declare fruit cakes “too decadent’, style won out when Queen Victoria served Fruitcake as her wedding cake,

When your father (Papa) and I were married in 1967, we had a white wedding cake which we cut for guests to eat at the reception. We also had a fruitcake, cut up and sent home with the

guests to sleep on!

But, of course, you want to know where this recipe came from!

Well, I don’t know the origin, for me it will always be “Grammie Stewart’s Fruitcake”. The recipe is at least 80 years old. Not a lot has changed in the recipe in that time except….it

would have taken Grammie a lot longer to prepare than it does me: the recipe calls for 1½ lb of blanched almonds – she would have had to actually blanch the almonds, I can buy them already blanched; the recipe calls for 1 lb pitted prunes – she would have had to cook the prunes, let them cool and pit them herself, I can buy pitted prunes. Lastly, the recipe calls for specific measurements of lemon, orange and citron peels- which she could buy individually, but which more and more only comes as “mixed” peels. So things have changed!

Here is My Grammie Mabel Hunter Stewart’s Dark Fruit Cake

Ingredients:

1 lb. butter, softened

6 cups flour – use 4 of those cups of flour to mix with the fruit

9 eggs

1½ lb. (675 grams) citron

1½ lb. (675 gm) lemon peel

½ lb. (227 gm) orange peel

1 lb. (450 gm) pitted prunes

1½ lb. (675 gm) whole blanched almonds

1 cup strawberries

1 cup molasses

2 tsp each lemon flavouring and vanilla

2 tsp each cloves, cinnamon, allspice and mace

1 glass brandy or rum (2 oz)

1 tsp baking soda

4 lb. (1.8 kg) seedless raisins

4 lb. (1.8 kg) currants

1 lb. (2 cups) brown sugar

Notes and Method:

1) If you can’t find the 3 different types of peels, use mixed peel. I can usually only find the orange peel and so use a combination of that and mixed peel.

2) Cook the prunes in about 1/2 cup water until soft. Let cool.

3) In a very large bowl, mix together the fruit, fruit peel and almonds with 4 cups of flour.

4) In a separate mixing bowl, beat the eggs, butter, molasses, flavourings, spices, rum, soda, brown sugar and the remaining 2 cups of flour.

5) Combine the two mixtures in a very large bowl using your hands if necessary (I do!) until there is no sign of dry flour.

6) Pour into 3 brown paper lined and greased fruit cake tins and one 9”x9” cake pans. Put a pan of water on the bottom rack in the oven.

7) Bake at 280°F for 4 – 4½ hours. Remove and cool.

8) When cold, wrap in brandy soaked cheesecloth followed by plastic wrap and foil.

9) Let “ripen” for at least a month before eating.

Janet Stewart Lindstrom describes herself as a Maritimer, despite being a resident of Northwestern Ontario for several decades. Jan prepares her Grammie Mabel’s Fruit cake each holiday season. Thank you Jan, for these memories, and gratitude in warm spices.

- The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) was an agreement between the Canadian and British Commonwealth to provide training facilities and staff for the war effort. Sites were located across the country, with 3 sites in New Brunswick, Chatham, Moncton and Pennfield, with 2 supplementary air fields in Scoudouc and Salisbury to support the Moncton #8 Service Flying Training School. See this link for additional information on the Canadian program https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/maple-leaf/rcaf/2021/03/british-commonwealth-air-training-plan-carried-the-day.html and New Brunswick’s effort, https://nbaviationmuseum.com/bcatp ↩︎