Frying pan cookies and canned peas?

Recently, while browsing through some of the recipes in the My Mother’s Cookbooks collection I came across one of Mum’s handwritten holiday menus. A list of all of the special foods she planned to prepare, share and serve during the season. It contained all of the usual suspects, Squash Puff, Cornish Pasties, Whipped Shortbreads, Buttertarts, Doughnuts, Fruit bread, Sausage rolls, etc. including Frying Pan Cookies.

I remember frying pan cookies, they appeared perrennially each Holiday season, but I don’t recall them being anyone’s favourite. Mum spent weeks cooking and baking from her lovingly maintained list of each family member’s favourite foods. Come the Holidays some of each of the prepared favourites would be retained for everyone to share, the remainder packaged for the favoured family member to ‘take home’. Which of course helps explain the size and complexity of Mum’s Holiday menu.

Mum loved to discover new foods and managed to embrace the small bits of diverse culture and tradition she encountered, honouring and respecting those whose life and times intersected with hers, using food. At Holiday time that meant providing the best traditional experience for each and everyone at her table through their favourite holiday foods.

When my then boyfriend, now husband Ray, found himself with a last minute change of his holiday plans, of course he was invited to spend the Holiday at my parent’s home. The haste of invitation restricted Mum from learning about Ray’s favourite foods and her limited knowledge of his background precluded her from preparing something specifically for him.

Ray’s first Christmas with our family was already heading for the record books. Christmas dinner was being hosted by Eleanor, My sister in law Darlene’s Mother, aided by her son a professional chief. The meal was outstanding, variety of roasted meats, vegetables, salads, and desserts, oh the desserts. After a lovely meal and time spent catching up on the year’s events in our lives, Ray and I along with my parents began the hour long drive back to my parent’s home.

During the drive, the meal we had just consumed was lauded and appreciated by everyone. It was Dad, who’d pointed out delicious tho it had been, it had not been a ‘true’ Christmas dinner. He’d missed the turnip, and jellied salad had not replaced his favourite squash puff. Ray empathizing with Dad chimed in that yes, he’d missed the canned peas, with the turkey. Mum turned to meet his eyes in the darken car. “Now that is interesting Ray. Canned peas, to go with your turkey dinner. It is a good thing I have the turkey thawed, we will just have our true Christmas feast tomorrow”.

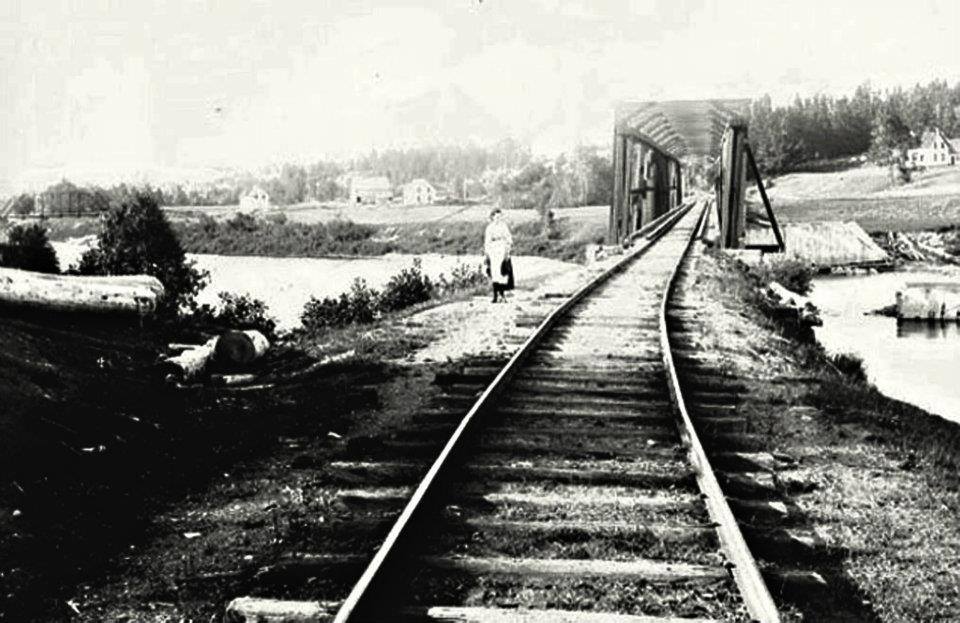

The next morning Boxing Day, Mum was up early with the turkey stuffed and in the oven before most of the family were roused for the day. My parents retirement home in the central New Brunswick community of Ludlow did not offer much in the way of retail experience, especially on Boxing Day. So I was surprised, as I wiped sleep from my eyes, to find Dad donning his jacket and boots, heading out to find an open convenience store. You see Mum did not have canned peas on hand.

Oh sure, there had been a time when canned peas had appeared on our family table but they had long since been replaced with the frozen variety. For Mum that did not mean they could be used in a pinch, not for Christmas dinner. Ray had said canned peas, canned peas he would have. Dad always Mum’s accomplice when it came to ‘doing’ for family, happily made the slog to the local Irving and snagged a can of peas.

Ironically, I was the one who nearly ruined her plan to assure Ray had his peas just the way he liked. Fortunately, I was saved from an agregious mistake, by Ray’s observation ‘Oh you are heating the peas?’ You see Christmas dinner canned peas are not a ‘vegetable’ or at least not served as a one, they are served cold as a condiment, similar to cranberry sauce.

As was her habit canned peas along with a considerable number of Ray’s other favourite foods were added to her list of Holiday favourites. When I began writing this piece, I was stumped about whose list of favourites included Frying pan cookies. As I considered the recipe it became clear…dates, cherries, coconut; simple, quick, one dish…Frying pan cookies were Mum’s favourite.

My folks are both gone now but they live on in the hearts and minds of those who shared their table and spent time on Mum’s list of Holiday Favourites. A little last minute Holiday baking is in my future, Frying Pan cookies will make an appearance this year. Wishing you and your family the very best of the Holidays and a healthy and prosperous New Year!

My Mother’s Cookbooks Frying Pan Cookies

Ingredients:

1cup white sugar

1 cup dates chopped

2 Tbsp butter

1 egg

1/2 tsp vanilla extract

1/4 tsp salt

1/4 cup candied cherries chopped

2 cups rice crisps

1/2 cup (or so) of shredded coconut

Method:

1. Place the sugar, dates, butter, egg, vanilla and salt in an electric fry pan cook for one minute.

2. Add cherries and rice crisps, stirring to combine.

3. Portion in to small balls and roll in coconut.

Acknowledgement: I acknowledge that the land on which I live and write about is the traditional unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Mi’kmaq Peoples. This territory is covered by the “Treaties of Peace and Friendship” which Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Mi’kmaq Peoples first signed with the British Crown in 1725. The treaties did not deal with surrender of lands and resources but in fact recognized Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) title and established the rules for what was to be an ongoing relationship between nations.