Atlantic Canadian Women of the cloth – 19th century and beyond – part 1

The running joke in our family was that it was breakfast, not the alarm clock that drove my Dad from bed in the morning. Dad loved breakfast, but his favourites were full on hot meals with loads of protein, quite often served with fried leftover potatoes. Although I eat protein at breakfast, the protein in my breakfast smoothie comes from dairy, vegetables, seeds/ grains, including hemp seeds/hearts and flax seeds1. Leftover potatoes often appear when I serve Breakfast for supper.

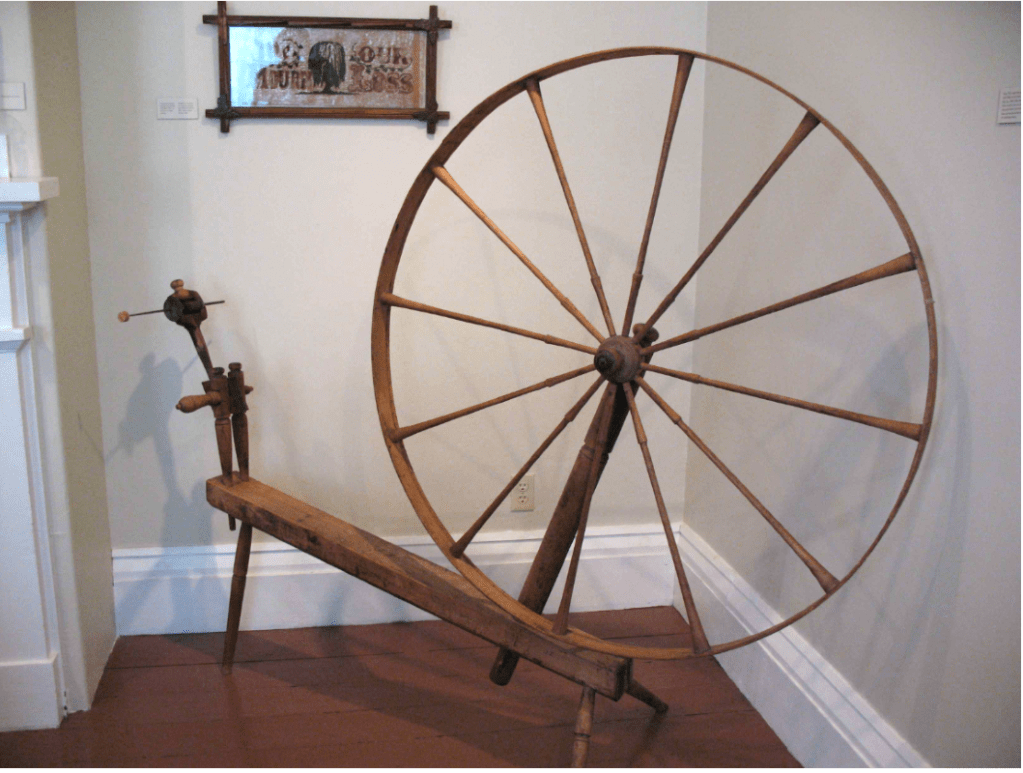

For more than a century spinning wheels have been a recognizable feature of our past. You don’t have to visit a museum to see them, although you will find more than one in most regional museums2. Spinning wheels still decorate grand old homesteads and suburban bungalows alike. Their success as decorative objects has made them representative of the entire homebased textile industry if not an entire era. In reality, spinning is a critical but single step among many in the production of cloth and other textiles. Even within the single critical step there is complexity and nuance which the story we know, misses. The first being not all spinning wheels are created equal, many are actually non-functioning replicas3.

When Sarah Tucker died in 1893, at 90 years of age, her occupation was listed as ‘Knitting’4. This factoid conjures images of grandmotherly Sarah, being so identified with the pretty dainties she knitted, it had become her ‘occupation’. It is likely, even in advanced aged, income was Sarah’s practical necessity and the products Sarah knitted were woolen socks, mittens, and long johns. Sarah was able to knit, and provide herself an income, even though she could no longer draw the fiber and spin the wheel. Atlantic Canada’s harsh climate, timber harvesting, fishing, and farming kept the whirl of spinning wheel, the click of knitting needles, the thud of the loom and the income they produced particularly for women, a regular part of life, long after machine production had replaced it in other areas5.

Despite being well schooled in the techniques and equipment used to produce textiles from fiber in her Ireland home, new mother Sarah did not bring her spinning wheel with her to New Brunswick. Ireland of 1823 was not the best place to raise a family, few resources, little work, meant no prospects beyond life in a city slum and work in a factory6. Sarah and her husband Thomas Tucker chose instead to become settlers to New Brunswick. The cost of passage involved extra fees for baggage, and limited items they could bring with them. If Sarah packed a tool to spin with, it was probably a drop spindle7.

Sarah’s drop spindle, came in handy for spinning, plying wool and other fibers, making flax twine for fishing lines, and for twisting hemp for rope, all things necessary in an Atlantic Canadian settler homestead. A spindle is not as efficient or fast as a spinning wheel. To spin the amount of yarn and linen she needed, Sarah required a spinning wheel. Although she might have fancied an Irish style Castle treadle wheel with the drive wheel mounted on top of the spinning assembly, and not arranged on a table like most other spinning wheels, she would have settled for what was available, provided it would accommodate a variety of fibers.

Ellen Taylor Williston’s spinning wheel might have come from the old country, she might even have had more than one. Like most European settlers economic opportunity was impetus for her Taylor family to immigrate from Scotland to New Brunswick. Ellen’s family despite little financial means had material resources and they had time others did not8. Resources did not mean Ellen had servants to spin and weave cloth for her family. As a child, like Sarah she grew up watching, learning and doing her part. By the time Ellen married Luther Williston, the Taylor family had added to their means and influence, a spinning wheel might well have been among Ellen’s wedding gifts.

It’s possible Ellen used a Walking wheel9 for some of her spinning. Although wool made up the majority of the fiber she processed, until the 1840’s her spinning included linen, including for warp thread. Great wheels are hand driven and require the woman to walk to first spin and then load the thread on to the spindle. Small wheels with a flyer assembly allowed the thread to be both spun and loaded on the bobbin from a seated position. The great wheel does have advantages for some types of fiber processing, such as spinning wool, particularly Worsted wool or cotton. Smaller treadle wheels allowed the woman to use both hands to control the fiber, especially important when spinning longer fiber like flax. Shorter fibers like wool and cotton are more easily spun on a Great wheel, at least according to some spinsters.

Despite a family history in North America of more than 200 years, Virginie Girouard Allain’s spinning wheel was not a family piece. If she chose a traditional Acadian style wheel, one with a flat rimmed drive wheel, a four legged straight table, and equipped with a distaff10, it was probably one made locally, possibly by her husband Thomas, using a wheel purchased from a local wheelwright. Virginie’s family’s expulsion from their homes in 1755 assured the tools in daily use in prosperous Acadia, did not survive for her to inherit and use.

Although Virginie didn’t have benefit of her Great great grandmothers spinning wheel, she did grow up absorbing the knowledge and skills necessary for using one. Virginie family’s experience in growing / raising and processing fiber of various types was deep, and continuous during and after the grand derangement. Acadian farmers had been the first in North America to cultivate a whole range of crops including wheat, hemp and flax, and it continued in their relocated homes. Traditional Acadian attire comprised of both wool and linen, was practical and affordable, especially if you grew/raised the fiber and did the processing.

Preparing wool for spinning is no easy task, but flax fiber is exponentially more difficult. The physical properties of Flax which make it advantageous even today made its harvest and processing into linen laborious and difficult. Virginie and Thomas Allain grew and processed flax on their farm, depending on their children and extended family to aid in its harvest and processing. Once ready for harvest, those with the strongest backs would pull the plants from the ground, beginning an investment in weeks of time and hours of physical effort just to get the flax fiber ready for spinning.

When Flax fiber is processed two types of fiber result, the long highly prized line fiber and the shorter tow fiber. True linen is made from line flax, which earned linen its iconic status. Line flax is long, strong, soft, beautiful, and ideal for cloth from which a host of industrial, household, and clothing products are made. Tow fibers are shorter and used for twines, rope and sack material. The longer tow and shorter line fibers were spun in to lower quality linen, which produced hard wearing, absorbent, quick drying clothing that was affordable, if more than a bit scratchy.

Even after cotton warps11 were in regular use, and most farmers stopped growing flax in Atlantic Canada, Its cultivation, processing into linen and linen cloth continued in areas where the population was of Acadian ancestry. Like Sarah’s knitting, this conjures for some a vision of downtrodden Acadian women, marginalized, hopeless, dressed in archaic traditional fashion rejecting modernity for the sake of maintaining old ways.

Reality of course was complex and nuanced. There is one fact which solidifies this complexity for me. Early Acadian settlers were self sufficient, they had to be, but self sufficiency came with the toll of constant monotonous effort, particularly for women.

The unearthing of 14 pairs of scissors in the archeological digs in areas of Beaubassin is interesting and revealing. The scissors which date from before 1755, range in size, function and form. Scissors sized for small hands confirm young girls were participating in textile production, that some of the scissors are for embroidery and others are heavily decorated suggest an inherent capacity and desire to find beauty and creativity in the mundane. Applying this basic desire to life after Expulsion, it does not take a stretch to imagine the desire to create and be with beauty helped motivate women like Virginie to engage the cultivation of flax and to produce the works of great beauty that is finely woven linen cloth.

Spinning wheels come in all shapes and sizes, some hand driven, some treadle powered, arranged on a slanted table or flat one, equipped with a distaff or not. A single style of wheel reigning supreme or belonging to a single country is as fool hardy as thinking a single version of a well loved recipe could top all others. Homebased textile production was a shared human experience, it benefited from exchanges of ideas, techniques, ingredients and technology.

I can say with confidence, Sarah, Helen and Virginie shared potatoes as well as spinning wheels. Potatoes grow well in many areas of Atlantic Canada and recipes containing them can be found in all major heritage groups of the region. Homegrown potato recipes, like all recipes have benefited from similar cross cultural influences as Homespun. Like homespun, recipes can have identical ingredients, same general method but a small adjustments in ingredients and/or technique can make a significant difference in the result.

Potato farls are simple potato based pancake, which are rolled, cut into 4 quarters or farls, fried and served with breakfast fare, eggs, bacon, etc. If Sarah called potato cakes farls, Ellen probably called them tattie scones… Virginie’s potato pancake recipe called for finely grated raw potatoes, combined with egg, flour, etc. and fried, Crêpes râpée! .

My Mother’s Cookbooks Potato Farls

Ingredients:

1lb / 450 grams of cooked mashed potatoes

3 Tbsp salted butter

1/2 c to 1 c all purpose flour (plus 2 T extra)

1 tsp salt

1 tsp baking powder

oil for frying

Method:

1. peel and pare 1 pound of potatoes, wash, bring to a boil in salted water, cook until tender;

2. transfer to a bowl, add butter and mash thoroughly;

3. add 1/2 c of the flour, salt and baking powder, mix thoroughly adding additional flour necessary to create a handleable and soft dough, divide into two balls, flatten and roll to 1/4 inch thickness;

4. cut into quarters, fry in a med hot pan in your oil of choice, butter, sunflower oil, bacon fat, etc. 3 mins each side.

5. spread with butter and serve with a full on hot breakfast.

Did you miss the introduction to “Atlantic Canadian Women of the Cloth – Homebased textiles 19th century and beyond”? See Homespun and Mrs Campbell. Part 2 of the series and the ending of Mrs. Campbell’s story Work, Frolics and Tragedy will be released 19 October 2024.

Footnotes:

- Flax meal and hemp hearts are wellness superfoods. 200 years ago, flax and hemp were used by most everyone, but not as food. Among the earliest crops cultivated flax has iconic status in the textile world. From ancient Egypt to the age of sail, flax and hemp were there, in everything from clothing to sails. Flax, and Hemp, yield their bast (stem) fiber which requires significantly more processing than either wool or cotton. Domination of flax fiber ended with increased production of cotton and hemp’s production dropped significantly with the arrival of plastic fiber rope. Hemp’s reputation as a fiber/food stuff has also been both misunderstood and under appreciated because of its family relationship to Marijuana. Flax fiber makes its appearance today in everything from paper money to car parts, linseed oil extracted from flax continues to be used in paints and stains, etc. Hemp is making a resurgence not just because of its seeds superfood status but as a more environmentally friendly option to manmade fiber, it appears in clothing, bed sheets, rope, etc. ↩︎

- The Canadian Census of 1871 asked Heads of household if they owned a loom, 40% responded, yes. Agriculture and industry schedules report large amounts of homespun produced. Based on this data, it is estimated more than 90% of households had a spinning wheel. Many were eventually donated to local museums. ↩︎

- Centennial celebrations of founding both the US and Canada saw a surge in interest in each country’s history. Spinning wheels quickly became representative of not just textile production but the entire colonial / settler period. Suddenly spinning wheels which had laid idle for decades, acquired value as decorative objects. They came out of attics and sheds, were oiled, polished, put on display or sold for a tidy sum. For those who didn’t have one, affordable replicas were also available. ↩︎

- Knitting is a method of producing textiles that involves using long needles to interlock loops of yarn. The textile produced is flexible and moves more with the body, lending its self to use in hats, mittens, scarves, long johns, sweaters, etc. Knitting was also used as a technique for producing fishing nets. ↩︎

- Homebased textile production peaked in Canada about 1871, at least 25 years after the US. Decades before the mechanization of the textile production in Europe, had pushed homebased textile workers out of their homes and into factories. The reason Atlantic Canada’s homebased textile industry remained active is sometimes explained as the result of the region being traditional and conservative to the point of backwardness. This view is being refuted by historians, and the factors delaying investment in mechanization are now understood to be a complicated mix of external and internal influences. ↩︎

- Ireland’s history of hardship created by the British Crown’s use of punitive tariffs to please English farmers and merchants at the expense of the Irish economy and its people, is reflected in the Irish homebased textile industry. When Irish farmers were faced with tariffs against their lamb, farmers sold wool, when their wool faced unfair taxation they processed it into cloth, when it was taxed, they grew flax, and processed linen. The proliferation of textile factories in Britain beginning in the early 19th century, saw the end of widespread homebased textile production in Ireland. Although Irish linen remains a gold standard for quality linen. ↩︎

- Spinning fiber, is twisting fiber together to create a single piece of thread. Drop spindles are the earliest known tool for twisting fiber in preparation to producing cloth/ textile. There are thousands of styles of spindles, but the idea is simple. A spindle is a stick or small piece of wood with weight on one end so it can be twisted so it will draw the fiber in to one smooth continuous thread. Some styles of spindles use added stones or whorls to assure spinning, others are carved to assure an easy twist. ↩︎

- Ellen’s Grandfather Patrick Taylor was a well known member of the New Brunswick political elite who arrived in Northumberland county New Brunswick in the period just prior to the American Revolutionary war, with his large extended family. The Taylor family have a minor Royal connection, which provided a small income to their mother’s Gordon family for generations. By the end of the 18th century inflation had reduced the value of the allowance requiring the family to seek new opportunities in North America. ↩︎

- The first innovation in spinning wheels were hand driven, the Great wheel or Walking wheel. Smaller treadle wheels did not replace the great wheel but afforded benefits for spinning longer fiber, such as flax. The flyer assembly, afforded the capacity to both spin and wind the yarn on the bobbin. Equipped with a distaff, the new style of wheel let the woman make use of both hands to control the fiber. Both styles of wheels continued to be used because they delivered differing benefits. ↩︎

- Distaff is a tool made of wood on which textile fiber is wound, so that it can be more effectively controlled by the spinster, allowing her to drawn the fiber evenly into a smooth thread. Distaffs were first developed to help a woman contain the fiber while spinning with a spindle. The distaff was tied under her apron strings on one side of her body, the spindle by her opposite knee, she could spin, prepare meals and do other household chores. Just as spindles had been added to a drive wheel, distaffs were incorporated into spinning wheel designs, particularly when used for spinning linen. ↩︎

- The warp of cloth are the strands of thread/yarn which are mounted/tied lengthwise on a loom, the weft of the cloth are the strands of thread/yarn which are added using a shuttle and which run crosswise to the warp. The warp/weft might be made of wool, linen or cotton. In 1840’s cotton became available in sufficient quantities to become an alternative to linen. ↩︎

Atlantic Canadian Women of the Cloth – Homebased textile Series Reference list:

- Bitterman, R. “Farm households and wage labour in the Northeastern Maritimes” Labour/LeTravail, 1993. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/llt/1993-v31-llt_31/llt31art01.pdf

- Rygiel, J. A “Women of the cloth – weavers in Westmorland and Charlotte Counties New Brunswick 1871 -1891”; UNPUL thesis Carleton University, 1998.

https://repository.library.carleton.ca/concern/etds/37720d - Rygiel, J.A. “Thread in Her Hands –Cash in Her Pockets; Women and Domestic Textile Production in 19th-Century New Brunswick” UNPUL thesis Carleton University,

- MacLeod, E. and MacInnis, D.; “Celtic Threads: a journey in Cape Breton Crafts”; Cape Breton University Press, Sydney, NS. 2014

- Introduction to the Spinning Wheels collection in the National Museum of Scotland https://blog.nms.ac.uk/2020/12/14/introduction-to-the-spinning-wheel-collection-in-national-museums-scotland/

- Goodrich, W.E. “DOMESTIC TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN EARLY NEW BRUNSWICK” Keillor House Museum.

- Toal, Ciaran “Flax to Fabric – The history of Irish linen and flax” Lisburn Museum https://www.lisburnmuseum.com/news/history-of-irish-linen-flax/

- Dunfield, R.W. “The Atlantic Salmon in the History of North America” Fisheries and Oceans Canada 1985. https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/library-bibliotheque/28322.pdf

- “Flax, Farming and Food: How Scottish – Irish Immigrants Contributed to New England Society in the 18th Century”, Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Mass. https://worcesterhistorical.com/worcester-1718/flax-farming-and-food-how-scotch-irish-immigrants-contributed-to-new-england-society-in-the-18th-century/#:~:text=Accustomed%20to%20spinning%20wool%20and,fever’%20in%20the%20local%20population

- Wallace -Casey, Cynthia “Providential Openings – The Women Weavers of Nineteenth-century Queens County, New Brunswick” Material Culture Review. 46, 1 (Jun. 1997). https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/MCR/article/view/17740/22230

- Eveline MacLeod and Daniel W. MacInnes “Celtic Threads: A journey in Cape Breton crafts” Cape Breton University Press 2014.

Acknowledgement: I acknowledge that the land on which I live and write about is the traditional unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Mi’kmaq Peoples. This territory is covered by the “Treaties of Peace and Friendship” which Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Mi’kmaq Peoples first signed with the British Crown in 1725. The treaties did not deal with surrender of lands and resources but in fact recognized Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) title and established the rules for what was to be an ongoing relationship between nations.

Enjoyed reading this story. I recall visiting the Acadian Village with my grandmother. She was attacked to the spinning wheel as she too as a girl in Quebec learned the entire process of producing skeins of wool for knitting 🧶.

LikeLike

Wonderful history!

LikeLike