A sheep shearer’s war effort, and My Mother’s Cookbook’s lobster roll.

This blog is 3rd in the series Atlantic Canadian Women of the Cloth – Homebased textile production.

Happy to reshare this blog from 2024, about one woman’s war effort, and a recipe for lobster roll too.

I have difficulty believing people order lobster in the shell in high end restaurants. It’s not that I don’t see lobster as luxury food, or that I don’t love the taste. For me a ‘feed’1 of lobster from the shell, is an outdoor activity. One that requires, all the tools, a newspaper covered picnic table, and freedom to let the juices drip off my elbows. Fortunately, I am local to two lobster fishing seasons, and to a large lobster processor. I have options and unless it is a family lobster boil, I usually buy fresh cooked (same day) and shelled by the processor. A feed of lobster is very much a luxury in our home.

Charlotte (Lottie) Melanson2 loved the physical demands of farm life but when it came to suppling herself an income her options were limited. The time Lottie’s father John Melanson spent working as a carpenter, assured his children were well equipped with skills like, sloping pigs, milking cows, tilling, planting, harvesting crops, and shearing sheep. From an early age Lottie preferred outside work, and did not take well to life in the classroom or one involving refined womanly activities.

In 1930’s Nova Scotia paid work was still highly gendered, women could choose jobs in retail, as housemaids, as factory workers, they could be teachers, or nurses but not paid farm labourers. Acadian women like Lottie and her sisters, faced the additional disadvantage of open and accepted discrimination against them for nothing more than their being Acadian. Many single women left Atlantic Canada for work in the factories or large homes of the “Boston States”3. If like Lottie, they wanted to stay local it often meant working in a lobster cannery.

Fishing lobster for export began in Atlantic Canada as soon as canning technology allowed the preserving of the tasty fish. When markets in New England and Britain beaconed, Atlantic Canadian fishers stepped up. The Lobster industry like any built on a luxury item, is subjected to market forces which are unpredictable and capricious4. Boom bust cycles effected fishers and processors alike from the very beginning. Market cycles which took lobster from ordinary food on Atlantic Canadian dinner tables to New York and London luxury restaurants, delivered it back with regularity5.

The period between the first and second wars was dominated by the Great Depression, high unemployment and widespread suffering. The depression halted a period of mechanization, the move away from subsistence farming and development of specialty farms. Textile production moved from spinning wheels to factories6 that depended upon imported wool. Although some farms still raised sheep, by the end of the 1930s they were in far fewer number.

Canada’s declaration of war on Germany in 1939 further entrenched the austerity began during the Depression but finding work was no longer the problem. Self sufficiency intensified further, cows and sheep repopulated farms and front lawns became vegetable gardens. Choosing homegrown and homespun became patriotic7 again, and the lobster on dinner tables and in school lunch cans was rebranded as patriotic too.

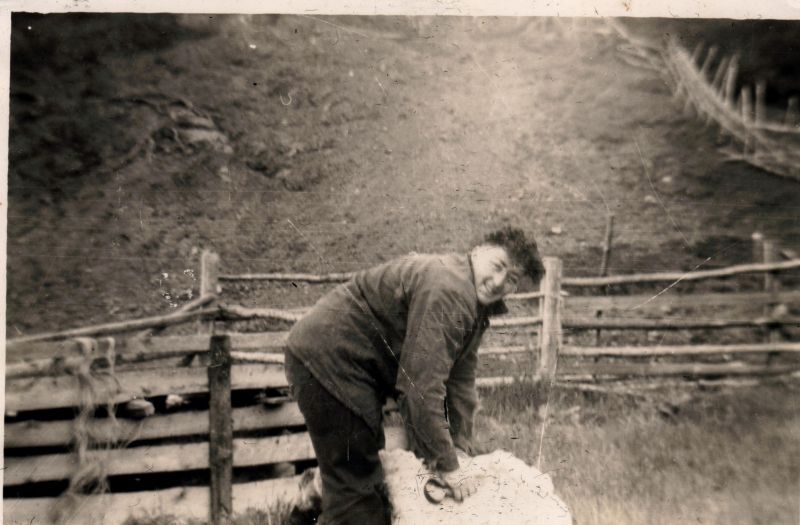

The recruitment of troops from rural Canada, emptied farm fields of labourers and raised a new problem. Who would till the soil and raise the animals? Just like in armament factories, the answer was women, women were now welcomed as employees on farms and in farm fields. For Lottie the war was an opportunity, she put her skills to work in aid of her country and earned income while her husband John MacPherson served overseas. Lottie found her niche as a farm hand with a particular skill set, she was a fast, efficient and effective sheep shearer.

During shearing season, Lottie moved from farm to farm in Antigonish, Guysborough and Inverness counties shearing sheep as she went. As an itinerate worker, Lottie depended upon farm families to host her during her time shearing their sheep. Lottie took to life on the road well, she used her work hours to hone her skill as a shearer and spent her leisure hours enjoying the company of her host families, attending local parties and social events.

Lottie, was a sturdy farm woman, tall, strong and willing, she was also what my Mum called ‘rough around the edges’. Lottie challenged gender norms with a salty tongue8, and a reputation for being able and willing to use her physical strength to contain wayward men as easily as the sheep she was shearing. The strong affection for Lottie held by those who remember her from those years, proves Lottie was more than a man-ish woman with a skill set. Her love of telling ghost stories to the children in the families she visited, and the respect other women had for her proves a depth of character beyond her sheep shearing capacity.

As a shearer few could surpass her ability, using only hand powered shears9, Lottie averaged about 80 sheep per day. In 1945 Lottie sheared more than 5700 sheep in her work season, and proved her capacity to shear a sheep in a record 2 minutes 45 seconds.

The end of second world war began a period of intense modernity, sheep raising, and homebased textile production waned. Lobster stopped being a patriotic food choice and disappeared from lunch cans. Lottie’s war effort ended too, sheep ranching for textile production all but stopped in the region, only resurging minorly after Lottie was beyond her ability to shear.

By the time I encountered Lottie, her physical health was failing but her reputation as a champion sheep shearer remained intact. I wish I had taken more time to know her and learn more about her life, I might have confirmed the good possibility, that some of those farm house tables delivered Lottie a feed of lobster.

Because I purchase lobster already cooked and shelled, I can serve it as lobster salad or build a fancy version of the school lunch box sandwich, the lobster roll .

My Mother’s cookbooks Lobster Salad / Roll:

Ingredients:

3 cups of chopped lobster

1/2 finely chopped celery

1/4 c My Mother’s Cookbook cooked salad dressing

up to 1/4 c Mayonnaise

salt and pepper

Method:

1. Place ingredients in a bowl and mix to combine, adding 1 T at a time of the mayo until it reaches desired consistency.

2. Serve with sides of potato salad, and mixed greens, or toast a brioche bun, slather with garlic butter and stuff with lobster salad.

My Mother’s cookbook cooked salad dressing:

Ingredients:

3 T flour

6 T sugar

1 egg

2 tsp dry mustard

6T white vinegar

1/2 c milk

2 T butter

Method:

1. In a medium sauce pan, combine flour, sugar, mustard together and mix well:

2. Add vinegar and egg which has been beaten, mix well;

3. Add milk and place over medium heat;

4. Stir constantly until the sauce reaches a soft boil and thickened,

5. Remove from heat, add butter, permit to cool and refrigerate.

*** Homemade boiled salad dressing can be used to replace sweetened dressings in potato salad, chicken salad, Cole slaw, etc.

Footnotes:

Atlantic Canadian Women of the Cloth – Homebased textile Series Reference list:

- “Flax, Farming and Food: How Scottish – Irish Immigrants Contributed to New England Society in the 18th Century”, Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Mass. https://worcesterhistorical.com/worcester-1718/flax-farming-and-food-how-scotch-irish-immigrants-contributed-to-new-england-society-in-the-18th-century/#:~:text=Accustomed%20to%20spinning%20wool%20and,fever’%20in%20the%20local%20population

- Bitterman, R. “Farm households and wage labour in the Northeastern Maritimes” Labour/LeTravail, 1993. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/llt/1993-v31-llt_31/llt31art01.pdf

- Rygiel, J. A “Women of the cloth – weavers in Westmorland and Charlotte Counties New Brunswick 1871 -1891”; UNPUL thesis Carleton University, 1998.

https://repository.library.carleton.ca/concern/etds/37720d - Rygiel, J.A. “Thread in Her Hands –Cash in Her Pockets; Women and Domestic Textile Production in 19th-Century New Brunswick” UNPUL thesis Carleton University,

- MacLeod, E. and MacInnis, D.; “Celtic Threads: a journey in Cape Breton Crafts”; Cape Breton University Press, Sydney, NS. 2014

- Introduction to the Spinning Wheels collection in the National Museum of Scotland https://blog.nms.ac.uk/2020/12/14/introduction-to-the-spinning-wheel-collection-in-national-museums-scotland/

- Goodrich, W.E. “DOMESTIC TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN EARLY NEW BRUNSWICK” Keillor House Museum.

- Toal, Ciaran “Flax to Fabric – The history of Irish linen and flax” Lisburn Museum https://www.lisburnmuseum.com/news/history-of-irish-linen-flax/

- Dunfield, R.W. “The Atlantic Salmon in the History of North America” Fisheries and Oceans Canada 1985. https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/library-bibliotheque/28322.pdf

- Wallace -Casey, Cynthia “Providential Openings – The Women Weavers of Nineteenth-century Queens County, New Brunswick” Material Culture Review. 46, 1 (Jun. 1997). https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/MCR/article/view/17740/22230

- Eveline MacLeod and Daniel W. MacInnes “Celtic Threads: A journey in Cape Breton crafts” Cape Breton University Press, Sydney, NS 2014.

- MacMillan, A.J. “A West Wind to East Bay: Short History and a Genealogical Tracing of the Pioneer Families of the East Bay Area of Cape Breton.” Music Hill Publishing, Sydney, NS 2001.

- Campbell, Joseph “Information regarding the avalanche at John Campbell’s farm 5 Feb 1856”, a recording by Mrs. Archie MacDougall 25 July 1966. In the holdings of the Beaton Institute, Sydney, NS.

- Roach Pierson, Ruth. “Canadian Women and the Second World War” The Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa 1983.

Acknowledgement: I acknowledge that the land on which I live and write about is the traditional unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Mi’kmaq Peoples. This territory is covered by the “Treaties of Peace and Friendship” which Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Mi’kmaq Peoples first signed with the British Crown in 1725. The treaties did not deal with surrender of lands and resources but in fact recognized Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) title and established the rules for what was to be an ongoing relationship between nations.