Cape Breton Oatcakes – A milling frolic favourite.

This blog completes… Homespun and Mrs. Campbell and is 2nd in the series Atlantic Canadian Women of the Cloth – Homebased textile production.

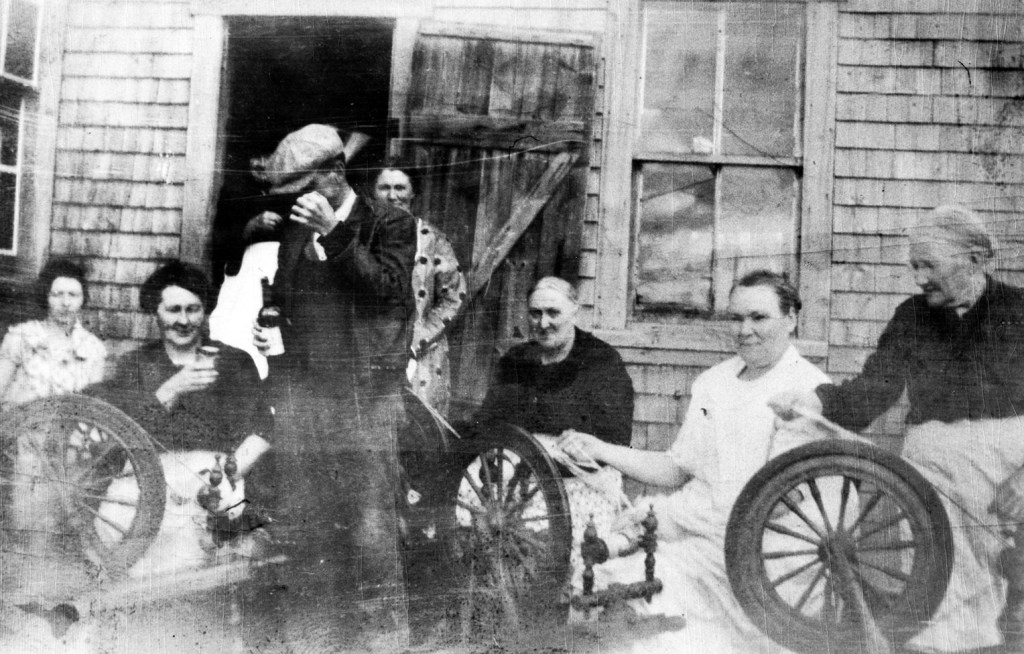

Today, crafters buy cotton / yarn in the colours they desire and get busy weaving, knitting, crocheting, etc. Homebased textile producers no longer need to raise and shear sheep, wash, pick, card, spin, dye, weave or full1 fabric. The tradition of women sharing work, particularly the activities of homebased textile production is well documented in many cultural traditions, none more than in Scotland.

The rich Gaelic tradition of songs and storytelling, combined with work were an important cultural vehicle. Assuring local history was recorded in memory if not in ink. From the shearing of sheep onward, where necessary and possible Scottish women shared their textile work, accompanied by their work songs, and food.

Janet Hendry MacDonald2 and Mrs. John Campbell3 willingly participated in work frolics hosted by family and neighbours, they knew they could count on a full house when they had laborious and/ or tedious work to do. Frolics not only provided a means to accomplish work, they provided an opportunity for social contact and alleviated the grind of the constant effort required to sustain a household.

Despite having a Scottish born father, and a husband with roots in the Western Isles, Janet’s language of life was English not Gaelic. Janet was well read, enjoyed poetry, keeping up with current events and for a time kept written records of her daily life. Janet’s diaries give us a glimpse into her life and her production of textiles. In today’s terms Queens county, New Brunswick was not ethnically diverse but there was diversity of backgrounds, culture, tradition, experience, skills and resources. Among Janet’s neighbours were families with generations of history in North America, some like her mother’s family were Loyalists from New York. Others like her husband, Alexander MacDonald’s family were Scots who settled first in North Carolina, or Pennsylvania, as her Grandfather and father had planned to do.

Janet’s diaries include references to spinning bees, quilting and sewing bees, but not carding bees or fulling frolics. By the time Janet and Alexander were establishing their homestead in McDonald’s Corner, Queens county, services like carding and fulling of wool cloth were being offered by local mill operators, who might also mill grain, or even lumber. The benefits to Janet’s textiles of machine carding, can’t be over stated, uniform carding leads to easier spinning and better yarn, better yarn leads to better…etc. Mechanical fulling saved loads of physical labour and assured uniformity of processing, which required skill if done by hand.

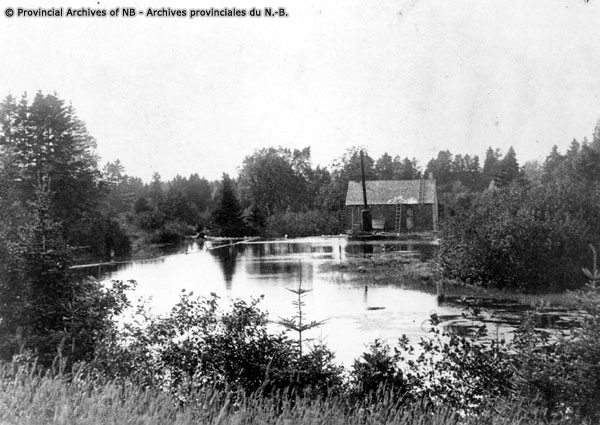

Mrs. John Campbell was a Highland Gael, it is possible she might have spoken English, but her language of life was Gaelic. I can say these things with some confidence, despite the absence of specific documentary proof. The diversity inherent in Queens county, NB, did not exist in Big Pond Cape Breton in the 1850’s. Although Cape Breton island had initially seen European settlement by the French and Acadians, the 19th century saw large numbers of Highland Scots immigrate to the area.

Despite fleeing dire economic realities in Scotland, families like the Campbells, MacDougalls, MacPhersons, etc. did not receive support or assistance from the Crown. Any immigration incentives from their previous landlords did not extend to previsions. Their response to this insecurity was to choose locations near those they knew. So family and neighbours from home, became neighbours in their new home.

Many of those who Mrs. Campbell knew and shared life with were former residents of the Western isles of Scotland, like the island of Barra, as were both the Campbell and McDougall families. Of course Cape Breton Scottish enclaves did interact, but for a significant period following arrival, language and religion drove contact, relationships and economic development.

Services like carding and fulling mills were slower to develop in some areas of the Atlantic region, unlike Queens county NB investment in the milling of wool in Cape Breton did not begin immediately. The combination of physical isolation, differences in language and religion served to create a unique cultural milieu. Mrs. John Campbell depended upon many of the traditional ways of producing yarn and cloth, just as she depended upon other women to help full her homespun.

7pm Feb 5th 1856 Big Pond Cape Breton.*

Gently swaying the whimpering child in her arms, Mrs. John Campbell reached to tuck a fringe of brown hair back beneath her Kerch4, she was sure it looked as tired and rumpled as she felt.

Turning toward the older woman who sat knitting in a chair to the left of the fire. “I am going to lay with the child awhile, maybe she will finally sleep.” Her voice sounding slightly hoarse to her own ears, too much singing and not enough sleep.

“I think you’d best just head to bed. I’ll be sending the girls to bed in the loft shortly. The men will soon be finished with the grain and want an early night. They’ll no be wanting women underfoot.” her mother in law replied, knowing with the house crowded, John and neighbour young MacDougall would bunk on the floor in front of the fireplace.

“I will” She replied thankfully, stifling a yawn. Biding John’s mother and nieces a “Oidhche mhath”5 she collected a candle from the mantle, pausing only briefly to light it before turning toward the bedroom.

Raising the candle high enough to peer in to the smaller of the two box beds6 which lined one side of the room, she was relieved to see both of the older children were sleeping soundly. The music and laughter had disrupted their sleep, leaving them tired and cranky. Just like baby Mary, she thought looking down into the child’s sweet face, grateful that she was finally quiet, if not sleeping.

Carefully sliding the child on to the larger bed she arranged the cradle next it, so she could transfer her later. Removing her kerch and outer clothing she blew out the candle and tiredly eased on to the bed beside her daughter, who seemed content to chew on her tiny thumb.

A soft smile of satisfaction crossed her lips as she mulled over the frolic. She was well pleased, her clo mor had actually drawn a compliment from her Mathair cheile7. The evening had been a great success, the arrival of MacPherson with his fiddle an unexpected treat. Even Mathair cheile seemed to enjoy herself, which was never guaranteed. The older woman, like many of her generation, preferred the old ways.

The only tension filled moment had been between MacDougall and her Mother in law. When the senior MacDougall, who taken over singing when the men joined the waulking8, made it known he considered the cloth needing only one more course to be fully milled, sparks flew.

Her Mathair cheile insisted there would be no seanchas, or dannsha9 until the her meur10 told her the cloth was milled. Thankfully, MacDougall agreed out of respect for the older woman, helped along by her being Grandmother to the MacPherson girl his son fancied11. John said he was sure, MacDougall nearly biting through his tongue when his mother held out for four full verses, would surely make it into one of his songs12. But the older women’s success put her in a good mood, the music and food met her approval, even the sweetened oatcakes. Yawning, her eyes closing as she drifted toward sleep.

A strange rumbling sound jolted awake her, she reached instinctively for the baby…

* This is a fictionalize account.

Sometime on the evening of the 5 Feb 1856, the John Campbell homestead was destroyed by a snow slide. When Stephen MacDougall did not return home as planned on Wednesday morning, his brother went in search of him. Finding no sign of a house or barns on the Campbell property, he raised the alarm.

Stephen MacDougall, and John Campbell were found trapped in the debris and unable to aid the women and children. John’s mother Mary Campbell was discovered in a corner under a cabinet, she too survived the ordeal. Baby Mary was found unharmed lying next to her mother on the box bed. In total five people lost their lives, Mary Campbell, Mary MacPherson, Mrs. John Campbell and the two older Campbell children.

The records of the tragedy at John Campbell’s farm are very sparce13. In the absence of victim names, details of destroyed buildings, livestock and potatoes being found more than 200 feet away, seem to our sensibilities a bit cold and lacking basic humanity. It would be wrong to view the past by our current experience.

Record keeping during the 1850s was uneven and reflected the social conditions at play. Newspapers of the time demonstrated a generalized disinterest in women’s lives, and marginalized further those who spoke Gaelic and were Roman Catholic. A tragedy that killed 3 women and 2 children engendered less interest in publishers than the cautionary tale about snowslides endangering other farms and livestock. So the personal memory of the event and those who died was left to family and community.

It is hard to imagine the scars an experience like this leaves on survivors. John Campbell lost almost everything in the blink of an eye, in what can only be described as a freakishly rare event. His wife, two of his children, and his nieces, his house, farm, and most of his livestock, all gone. The older Mrs. Campbell lost 4 grandchildren and a daughter in law, she like John and Stephen would surely be haunted by the hours of helpless suffering as she listened to the desperate cries from her dying loved ones.

John Campbell eventually rebuilt a home and farm on the property, although his new house was located as far from the hill side and previous site as possible. He also remarried, his second family beginning to arrive some 5 years after the loss of his first wife and children. Sadly, John Campbell died himself in February 1870 leaving his wife to raise their young children aided by kin and community.

The tradition of milling or fulling frolics lingers today in Cape Breton. As was always the case milling frolics are about language, music, tradition, and the joy of sharing, the only thing missing today is the work. Cape Breton’s unique ‘Scottish’ culture should not be mistaken as just the result of people repeating what they knew. It was never the case, from the onset Scottish settlers adapted. They made modifications and adjustments in what and how work was approached, new techniques and resources were always being applied.

When Mrs. Campbell worried about her Mother in law’s love of the old ways, she might have been referring to everything from men being involved in waulking the cloth to whether frolic oatcakes should contain wheat flour and sugar. Traditions don’t continue without alteration and without a good reason. I would say both Cape Breton oatcakes and milling frolics have proven themselves to be good reasons.

My Mother’s Cookbooks Cape Breton Oatcakes

Ingredients

2 1/4 c scotch oatmeal or rolled oats

2 1/4 c whole wheat flour

1 tsp salt

1 1/2 tsp baking soda

1/4 c each brown and white sugar

1/2 c + 2 Tbsp cold water

1/2 c lard

Method:

1. Preheat oven to 400 degrees F.

2. Combine oatmeal, flour, salt, soda and sugar together in a bowl;

3. Cut lard into the dry ingredients;

4. Add water and stir to combine;

5. On a well floured board, pat into a rectangle, then roll out the dough to 1/2 inch thick;

6. Cut in to rectangles or continue to triangle shapes;

7. Place on a cookies sheet and bake for 12 -15 minutes or until golden brown.

Footnotes:

- When homespun cloth is removed from the loom, the weave is course, rough, loose and thin. To convert cloth in to soft, warm and wearable cloth, mechanical agitation (beating and pounding) combined with either water or other substances like urine to shrink the fibers. All woolen Cloth required some milling, to reach Clo Mor stage, the cloth would be milled until is was thick and essentially water proof. ↩︎

- Janet Hendry MacDonald born 7 Feb 1795 Cambridge, Queens county, New Brunswick Canada, died 22 Apr 1887 McDonald’s Corner, Queens county, New Brunswick. Janet’s father George Hendry born c. 1764 Elgin, Moray, Grampian, Scotland died 1830 Wickham, Queen, New Brunswick. Janet’s Mother Susannah Belyea born c.1781 Cortland Manor, Westchester, New York. died 1842, Cambridge, Queens, New Brunswick. Janet married 9 July 1818, Alexander ‘Black’ MacDonald born 4 October 1794 Hillsborough, Albert, New Brunswick died 29 March 1880. Three of Janet’s siblings Elspeth, Mary and James Hendry married Alexander’s siblings, Lewis, Donald and Delilah MacDonald. The MacDonald family operated a grist mill in Cambridge, Queens, NB. Janet and Alexander MacDonald farmed the portion of George Hendry’s property which was her inheritance. ↩︎

- Mrs. John Campbell, birth date, location, and name unknown, died 5 Feb 1856, Big Pond, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. She married John Campbell born ~1810 probably in Barra, Scotland died 22 Feb 1870 in Big Pond, Cape Breton. John was son of Donald and Mary Campbell, who settled in Irish Vale, Cape Breton. Some of John’s siblings settled in Middle Cape, and Grand Narrows, Cape Breton. ↩︎

- A kerch is a traditional head covering worn by married Scottish Gaelic women. Made of white cotton, the white crispness of her kerch was a sign of a woman’s quality. ↩︎

- Oidhche mhath – Good night greeting in Scottish Gaelic. ↩︎

- A box bed is a type of wood framed cabinet bed often incorporated in to the walls of a house. When equipped with curtains or shutters box beds offered additional privacy. ↩︎

- Mathair cheile Scottish Gaelic term for Mother in law. ↩︎

- Waulking, Milling, fulling cloth are terms used to describe the process of shrinking wool cloth. In the Western Isles, women were primarily responsible for milling fabric. The addition of men, and the extension of the activities into the evening hours contributed in large part to milling frolics continuing in Cape Breton even today. ↩︎

- Seanchas – storytelling, dannsha – dancing in Scottish Gaelic. ↩︎

- Meur is finger in Gaelic, determining how much shrinkage cloth had experienced involved measuring the cloth prior to milling and regularly during processing. The measurement tool was a woman’s finger. ↩︎

- Social events, including milling frolics were opportunities for courtship. ↩︎

- Gaelic milling songs, are essential to delivering a fine evenly milled cloth. The cadence of the song helped to assure consistent and even milling. Cape Breton singers and bards were inspired by real events, funny happenings, conflicts and excesses were the stuff of their creativity. When Mrs. Mary Campbell insisted on her finger measurement she risked regular embarrassment at the hands of local bard. ↩︎

- The details of the avalanche at John Campbells farm are those related for generations by the people of Big Pond. Written accounts, and recorded oral accounts were not contemporary to 1856, some only recorded more than 100 years later. Those written resources are provided in the reference list. ↩︎

Atlantic Canadian Women of the Cloth – Homebased textile Series Reference list:

- “Flax, Farming and Food: How Scottish – Irish Immigrants Contributed to New England Society in the 18th Century”, Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Mass. https://worcesterhistorical.com/worcester-1718/flax-farming-and-food-how-scotch-irish-immigrants-contributed-to-new-england-society-in-the-18th-century/#:~:text=Accustomed%20to%20spinning%20wool%20and,fever’%20in%20the%20local%20population

- Bitterman, R. “Farm households and wage labour in the Northeastern Maritimes” Labour/LeTravail, 1993. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/llt/1993-v31-llt_31/llt31art01.pdf

- Rygiel, J. A “Women of the cloth – weavers in Westmorland and Charlotte Counties New Brunswick 1871 -1891”; UNPUL thesis Carleton University, 1998.

https://repository.library.carleton.ca/concern/etds/37720d - Rygiel, J.A. “Thread in Her Hands –Cash in Her Pockets; Women and Domestic Textile Production in 19th-Century New Brunswick” UNPUL thesis Carleton University,

- MacLeod, E. and MacInnis, D.; “Celtic Threads: a journey in Cape Breton Crafts”; Cape Breton University Press, Sydney, NS. 2014

- Introduction to the Spinning Wheels collection in the National Museum of Scotland https://blog.nms.ac.uk/2020/12/14/introduction-to-the-spinning-wheel-collection-in-national-museums-scotland/

- Goodrich, W.E. “DOMESTIC TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN EARLY NEW BRUNSWICK” Keillor House Museum.

- Toal, Ciaran “Flax to Fabric – The history of Irish linen and flax” Lisburn Museum https://www.lisburnmuseum.com/news/history-of-irish-linen-flax/

- Dunfield, R.W. “The Atlantic Salmon in the History of North America” Fisheries and Oceans Canada 1985. https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/library-bibliotheque/28322.pdf

- Wallace -Casey, Cynthia “Providential Openings – The Women Weavers of Nineteenth-century Queens County, New Brunswick” Material Culture Review. 46, 1 (Jun. 1997). https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/MCR/article/view/17740/22230

- Eveline MacLeod and Daniel W. MacInnes “Celtic Threads: A journey in Cape Breton crafts” Cape Breton University Press, Sydney, NS 2014.

- MacMillan, A.J. “A West Wind to East Bay: Short History and a Genealogical Tracing of the Pioneer Families of the East Bay Area of Cape Breton.” Music Hill Publishing, Sydney, NS 2001.

- Campbell, Joseph “Information regarding the avalanche at John Campbell’s farm 5 Feb 1856”, a recording by Mrs. Archie MacDougall 25 July 1966. In the holdings of the Beaton Institute, Sydney, NS.

Acknowledgement: I acknowledge that the land on which I live and write about is the traditional unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Mi’kmaq Peoples. This territory is covered by the “Treaties of Peace and Friendship” which Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Mi’kmaq Peoples first signed with the British Crown in 1725. The treaties did not deal with surrender of lands and resources but in fact recognized Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) title and established the rules for what was to be an ongoing relationship between nations.